Danish summary

Èt af Danmarks hidtil største citizen science projekter, Biodiversitet Nu, med over 27.600 deltagere og 1.1 millioner observationer afsluttes i 2021. Formålet med projektet har været: ”at skabe ny viden om hvordan biodiversiteten i Danmark har det, og samtidig inddrage den brede befolkning i indsamling af naturdata”.

Siden 2014 har projektet, med hjælp fra den danske befolkning og appen NaturTjek, indsamlet betydelige mængder data om naturen. Data, som har gjort det muligt at producere i alt tre forskningsmæssige leverancer, hvoraf den sidste udkommer slut 2021, kaldet ”Kommunernes Levesteder”. Forskningsleverancen er en analyse af NaturTjek-data omkring udbredelsen af 12 udvalgte levesteder for alle landets kommuner.

I november 2020 lancerede Københavns Universitet (CMEC) i samarbejde med Danmarks Naturfredningsforening ”Naturens Udviklingsindeks”, baseret på omkring 500.000 indsamlede artsobservationer. Resultatet blev 14 forskellige indeks, som viste, at den almindelige natur overordnet set er i fremgang i Danmark. Størst er fremgangen for den bynære natur, mens de almindelige arter ikke oplever forbedring hverken i vores naturområder med høj naturværdi eller i landbrugslandet. En peer-reviewed artikel forventes udgivet slut 2021.

Projektets eneste dobbeltleverance ”Kommunernes Naturkapitalindeks”, udviklet af Aarhus Universitet (DCE) og formidlet af Danmarks Naturfredningsforening, udkom primo 2017 og 2021. Naturkapitalen for Danmarks Kommuner findes nu i en digital version, som gør det nemt for borgere, medier, naturforvaltninger, jordejere og politikere at sammenligne kvaliteten af 392 forskellige indeks over den lokale natur på tværs af kommuner. Kommunernes Naturkapitalindeks har alene i 2021 været omtalt mere end 362 gange i nationale, regionale og lokale medier og væsentligt påvirket den lokale debat om biodiversitetens tilstand.

Projektets oprindelige ide om at forbedre kendskabet til begrebet biodiversitet har været nedprioriteret, grundet det omfattende arbejde med at mobilisere befolkningen via applikationen NaturTjek og generere tilstrækkelig data igennem projektets levetid. Det er dog værd at nævne, at projektet, ikke mindst i samarbejde med den meget lidt naturvidende maskot, Todd, spillet af Martin Brygmann, er lykkedes med at sætte fokus på begrebet. Analyser peger på, at medier og befolkning i løbet af projektets levetid har fået et bedre kendskab til hvad biodiversitet er, og en del af denne opadgående trend kan akkrediteres projektet.

Projektets endelige slutrapport ”Project Biodiversity Now - new eyes at nature”, som er skrevet på engelsk og udkommer slut 2021, peger på 10 væsentlige læringer fra Projekt Biodiversitet Nu. Nogle af de vigtigste pointer fra rapporten er, at danskernes villighed til at bidrage til citizen science er i absolut verdensklasse, men at naturkendskabet er signifikant lavere end forventet. Projektet fremhæver også appen NaturTjek og fremskridt i appteknologi helt generelt som en vigtig faktor for projektets succes, foruden vigtig læring om folkelig mobilisering og dataindhentning.

Slutrapporten i sin helhed samt de tre projektleverancer beskrives nedenfor og generelt på www.biodiversitet.nu.

Introduction

One of Denmark’s largest and most ambitious citizen science (CS) projects aimed at monitoring the development of biodiversity has reached its end. Armed with smartphones and the app “NaturTjek” more than 27,000 Danes participated in the citizen science project by registering 30 selected species and 12 habitats over a period of 6 years, gathering more than 1,1 million unique data points for analysis by scientists. The project deliverables, primarily based on the collected CS data, are threefold: The Danish Nature Development Index, The Nature Capital Index of Danish Municipalities and Habitats of Danish Municipalities.

Considering the scale of the project, Biodiversity Now is likely one of the world’s largest nature monitoring projects using citizen scientists as of end 2021. Hence its results, hard and soft alike, may be considered of value to a large global audience interested in engaging regular people, citizens if you will, to assist in the monitoring of biodiversity which we know is under significant pressure across our world. The following is not meant to be an exact evaluation of the project itself, but rather aims to cast light on the most significant findings of the national citizen science project, divided into 10 headlines. We, the project group, consisting of project leader The Danish Society for Nature Conservation, the two scientific institutions The University of Copenhagen (CMEC) and Aarhus University (DCE) as well as the foundation behind it all, Aage V. Jensen Naturfond, sincerely hope that our findings will be of value to future citizen science projects, or those engaged with the discipline, internationally.

1. The interest of contributing to citizen science in Denmark is world class

Denmark is no stranger to engaging its citizens in projects monitoring nature. Throughout the years, many different monitoring projects have made good use of more specialized Danes in various atlas projects tracking anything from fungi, butterflies, dragonflies and birds. What made Biodiversity Now different from previous monitoring projects was the scale and vast requirements for big data to carry out the analyses envisioned. Instead of focusing on groups of species or single species, the main goal of Project Biodiversity Now has been to engage the population in the extremely ambitious task of tracking developments, positive or negative, in Denmark’s overall biodiversity. This task obviously required massive amounts of data which all had to come from citizen scientists, collected as randomly as possible, yet in a steady stream from the project’s starting date May 2015 and onwards.

From the project onset, scientists at the University of Copenhagen (CMEC) considered 150,000 unique data observations yearly to be sufficient, but a project test run throughout 2014, bringing in only 5000 observations from 500 unique users, quickly revealed that this task would be overwhelming and challenging at best in its current form. Lessons learned from the test year of 2014, brought about a new native app called “NaturTjek” and a complete restructuring of the project leader organization’s project team, The Danish Society for Nature Conservation, to focus on engaging the Danish population using the new and improved application. Once the new application was launched and intensive marketing efforts to recruit citizen scientists throughout Denmark were enacted (more on that later), a remarkable amount of nature-interested Danes downloaded the app, registered themselves as users and went about registering some of the selected species and habitats listed in NaturTjek. When the NaturTjek application finally was made inactive October 2020, more than 100,000 people had downloaded the app, around 45,000 had registered themselves as users, and more than 27,000 had been actively involved in the projects as actual citizen scientists. These significant numbers of active participants are a clear testament to a nation of citizens truly engaged in the wellbeing of their local nature – as well as a testament to the possibilities of citizen science as a whole. However, it also clearly demonstrates the challenges faced by those managing citizen science projects when considering that 2/3 of those initially downloading the app never even participated once. Despite many attempts to engage passive users registered in the app, the amount of passive users remained above 40% throughout the project’s lifespan, according to project tracking files.

2. New technology enables monitoring of biodiversity development

One of the principal aims of Project Biodiversity Now was to test out the notion that an entire country’s biodiversity and its development over time could be tracked using scientific methods and big data collected by non-expert citizen scientists, randomly across years. This led to the selection of 30 indicative species for biodiversity in Denmark by scientists from The University of Copenhagen (CMEC) of which 500,000 observations were made by 20,000 citizen scientists by October 2020. 13 of the 30 selected species did not receive sufficient observations to be part of the main part of the analysis, whereas the 17 that did represented the more common of the species selected in Denmark.

While the analysis did not receive sufficient data to enable a more complete tracking of biodiversity in Denmark, and therefore were mostly able to show developments within common species, it did prove that the method using sufficient data from non-experts to track developments in biodiversity works. New technology, specifically related to mobile phone apps, makes this perhaps more achievable now than ever before in history. This project has proven that virtually any citizen anywhere with a modern smart phone and a capable nature registration app installed, can contribute to monitoring biodiversity in a particular area, municipality, country or continent for that matter – with ample project management and scientific monitoring. The starkest obstacles observed in the project was not the subsequent analysis of data or even problems with data quality, as previously envisioned. Instead, many citizen scientists reported registration fatigue and lack of motivation, as the selection of the 30 species stayed the same across the project duration as well as the registration process. Future projects using similar methods may design the project to include a broader selection of interesting species for the general public and make use of technology innovations to keep citizen scientists more motivated and engaged over time.

3. The Danes’ knowledge of species is lower than expected

When initiating a citizen science project of this magnitude, the selection of indicative species was considered crucial and considerable time was spent selecting species relevant for biodiversity while being easy to recognize and fairly accessible across the country. Despite the time spent selecting the 30 species, 13 of the species did not receive sufficient observations. This was surprising. Particularly, fungi and plants received too few registrations to be allowed into the main analysis, and this greatly impacted the final deliverable of The Danish Nature Development Index, solely based on collected species’ observations. It made it impossible to carry out a biodiversity development index for each municipality in Denmark, as first envisioned. But more importantly, it made it impossible to track changes across the entire spectrum of biodiversity, as the species left for analysis where those representing more common nature types. This lead the project team to examine it more closely via a questionnaire sent to the citizen scientists active in this part of the project. As expected, the answers demonstrate that many of the species believed to be easily recognizable from the project onset turned out to be more challenging for the general population in Denmark than what was expected, especially concerning fungi and plants. For future citizen science projects which require species registrations, such issues may be dealt with using modern technology such as artificial intelligence to assist app users, improve focus on education regarding particular species, or simply to chose other more simple and engaging species for citizen scientists.

4. Data follows the sun, roads and tracks

Once the thousands of data points started flowing into Project Biodiversity Now, basic analysis were made concerning the geographical coverage. Particularly interesting was the behavior of citizen scientists, considering that we had not selected specific areas to register beforehand. Where did they decide to register and were there any clear tendencies in the way they moved around in the landscape?

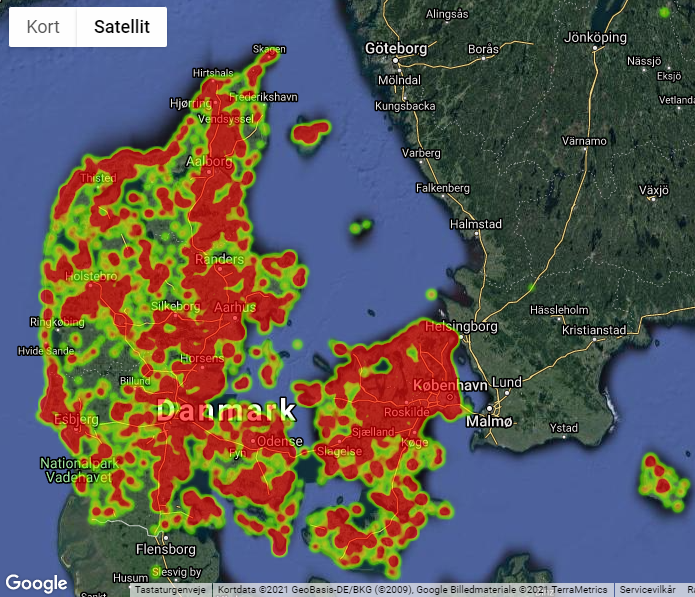

Perhaps not surprisingly, most observations in the project were centered around the mayor cities in Denmark, where most of the population lives. But an interesting fact related to the data was the connection between registration activity and sun hours. Besides of course representing a bias in the project data, it was surprising to the project team that weather had such a big impact on user activity. Another interesting observation from the project was how citizen scientists moved around and registered in the landscape. As show in the heat map below, most observations fall close to roads and tracks. This is probably also caused by the restrictions of movement in nature areas in Denmark, particularly privately owned where you have to stay on tracks and roads. But Danes showed similar behaviour in areas where they could move more freely around, perhaps pointing to some confusion about where and how you can act and move around in Danish nature areas. Naturally, such patterns in movement by those involved had an impact on the data.

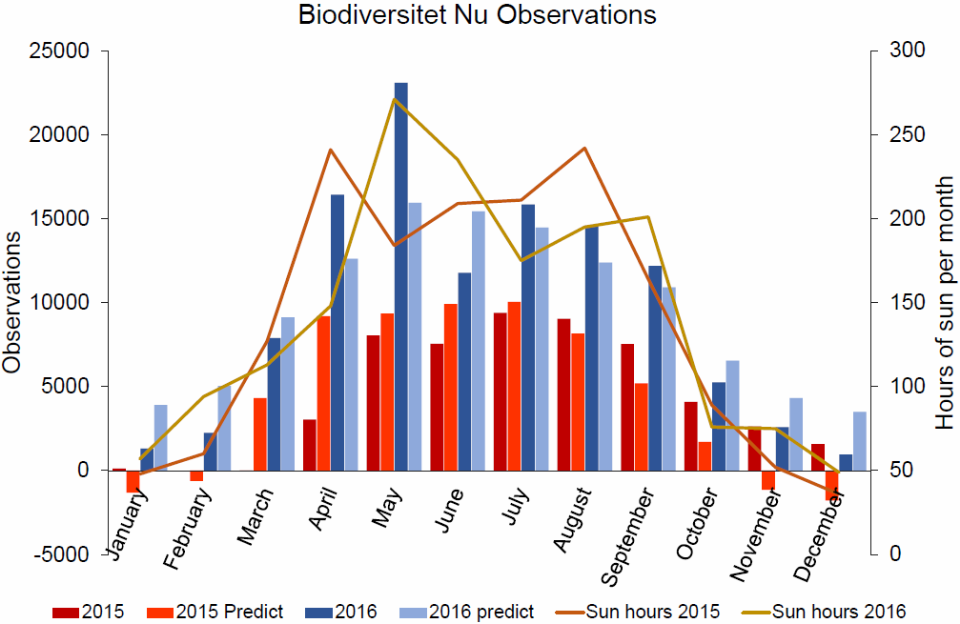

The figure shows the correlation between sun hours (yellow/orange lines) and observations made by citizens during the year. It shows that more observations are made when the sun is shining.

The heatmap shows the spatial distribution of observations in Denmark. Red colors represent places with many registrations and green colors represent places with fewer registrations. An area with no color indicates places with no registrations. The map is no longer interactive.

5. Strong partnerships are key to big data success

Being a national citizen science project with ongoing big data requirements across the country, Biodiversity Now was well aware that partnerships were needed to ensure a continuous flow of new app users which could eventually become actual citizen scientists and contribute to the project. Many partnerships were formed during the project’s lifespan, but most significant for the recruitment of app users were the partnerships with Danish scout organizations, public schools and large companies such as Concha y Toro (SUNRISE) and Danish/Swedish dairy company Arla.

Together these partnerships formed an important safety net for the project’s flow of new users and data observations. The scouts contributed significantly to the project with more than 6000 sold scout marks where scouts could earn the right to carry one of three project scout marks made in conjunction with Det Danske Spejderkorps and KFUM Spejderne, the two largest scout branches in Denmark as of 2021. Project Biodiversity Now also engaged schools by making teaching text book material and a bioblitz guide which teachers could download for free online. Both were frequently used in classrooms throughout Denmark. Finally, two commercial partnerships ensured thousands of app downloads. Arla assisted the project by marketing the app on milk cartoons, reaching thousands, if not millions of Danish consumers. The Chilian wine brand SUNRISE, owned by Concha y Toro, became the project’s closest commercial partner, offering both direct funding support, marketing efforts on SUNRISE wine sold in COOP shops across the country as well as support to a yearly event around the International Day of Biodiversity in May where the company donated money to a national biodiversity project for each observation made during the day. The event with SUNRISE also had scientific value in the later analysis, allowing for observations from each of these event days to be compared to the general tracking of biodiversity. We want to take this opportunity to thank all partners who contributed to Project Biodiversity Now. We owe a lot of the project success to your significant contributions.

6. Benchmarking of biodiversity sparks political debate

One of the main deliverables of Project Biodiversity Now was the launch of The Capital Index for Danish Municipalities (NKI) in 2017 and 2021. Lastly, the NKI was made digital, featuring more than 392 different versions of the index divided onto 98 Danish municipalities. The NKI is the first time local biodiversity is quantified and compared in terms of quality across municipalities in Denmark. With more than 362 media mentions in 2021 alone, the NKI ranges as the project’s most media covered deliverable by far. The NKI which benchmarks the quality of biodiversity across municipalities has sparked political debate concerning local biodiversity on an unprecedented scale. Several municipalities are now using the NKI as an integrated tool in their management of biodiversity, and are requesting more fine-grained benchmarking to improve their rating over time, compared to other municipalities. In terms of political impact, the NKI has proven to be more efficient than even imagined from the project onset. We see great potential for such instruments in other countries/municipalities worldwide interested in quantifying biodiversity and making it the competitive parameter that is deserves.

7. The balance between citizen and science remains a challenge

It is not uncommon to hear about the possible problems scientists face when venturing into using non-experts for large scale data collection. Certainly, this project also faced its own issues of balancing the need for quality data with the needs and wants of ordinary citizen scientists. As already mentioned, one of the obvious challenges was ensuring enough commitment and activity from app users throughout the project lifespan, despite the fact that the species were narrowly chosen and the project structure quite monotonous for the type of engagement required. This was overcome via the use of app technology, marketing and strong commercial and non-commercial partnerships, but might also have been overcome by a project design which took the citizen scientists and their needs more into account from the very beginning. Particularly on the deliverable Habitats for Danish Municipalities based on habitat observations from the app NaturTjek, the shortfalls became obvious. The project team was challenged on a whole range of issues, the main ones being an unexpected way of user registration from app launch resulting in a significant app update and change to the entire habitat registration process featuring a new swipe function which greatly improved data quality and accuracy but only from 2017, once a technical solution had been discovered, developed and properly tested.

The accuracy remained however a problem during the entirety of the project, as the requirements for the habitat observation were far more strict than those for the species. It also turned out that the types of participants interested in habitat registrations were a much more narrow group than those doing a simple and quick species registration. Having two modes of registration in one app might have been a practical solution from a scientifical point of view, but challenged both the technology of the app and the users of it, as well as the project leader team itself. The result became a habitat analysis with less impact than envisioned. Consequently, other large scale citizen science projects using complex digital technology should ensure diligent user tests before launch, continuously quality test and track CS data as it enters the database and carry out frequent test analysis on preliminary data according to predetermined analysis standards, if possible.

8. NaturTjek or Tinder? Big data demands exceptional marketing skills

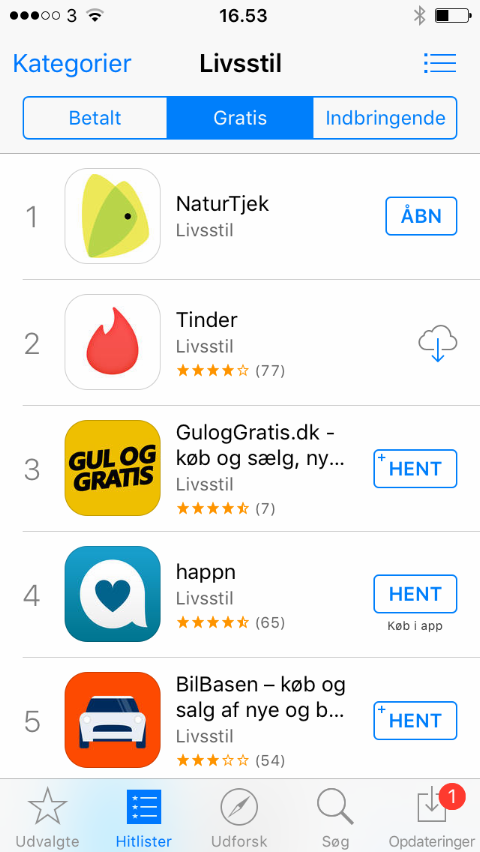

Imagine having to compete against apps like Momondo, Tinder or WhatsApp! This is reality once you enter the world of apps. Using citizen science and app technology in the pursuit of big data may seem like a brilliant idea, but in fact the real work starts once the app is released. The market for apps is increasing and demands specialist knowledge not only in terms of coding and app development, but also in terms of app system maintenance and ongoing marketing. Peak marketing enabled NaturTjek to outcompete apps such as Tinder on the domestic market on rare occasions. Herein lies one of the reasons for the national reach and success of Project Biodiversity Now. Using in-app marketing, social media marketing, Google advertisement and other forms of integrated marketing forms, app downloads which are rarely seen for citizen science apps/nature registration apps were achieved. Once your app reaches a certain number of downloads, it becomes much more visible on platforms such App Store allowing users to be exposed to your app which may never themselves have thought about participating in a citizen science project.

In-app engagement was also used, and often push messages sent out broadly resulted in +500/+1000 daily observations made and a subsequent higher engagement level the following days. One of the uniquely designed features of the in-app push system in NaturTjek was that it was designed to target users based on both registration/activity level and location. This ability to send out targeted push messages was further made operational by a data mapping function which showed the live data status for each municipality in Denmark. Many users made use of this map to increase or decrease their level of engagement, compared to the data requirements. But the project leader team also used the map to push for further engagement in municipalities with too few observations. Live access to data and project stats turned out to be crucial in order to maintain high engagement and nudge users to register more in some areas, without exactly telling them what to look for - which would go against the scientific methods used.

9. The 10 second check

For those not fully engaged in the world of apps, it can be hard to understand the mechanism and the dynamic nature of those platforms. Apps are quickly and harshly evaluated and simply erased, if they do not “measure up”. NaturTjek was developed with this in mind. The app needed to do its job of collecting data according to the standards set out by scientists, but it also needed to do it fast. Based on user feedback collected in the beginning of the project, a registration should take no more than 10 seconds, and preferably less. Anything beyond that, either due to an inefficient UX design or technical issues, would lead to user dissatisfaction and eventual deletion of the application itself. The balance between speed and data quality turned out to be an ongoing issue leading to app updates which in fact deliberately slowed the app down somewhat on some fronts, particularly in relation to habitat registrations where accuracy was particularly important. However, despite these alterations, the app maintained its speed characteristics which was reflected in an overall app user satisfaction of more than 90% - where many users praised its speed as a key trait.

As app technology develops and new technical features assist users, often unknowingly, many manual actions may be made redundant, thereby increasing the speed of registration even further. Modern smart phones use complex triangulation to calculate accuracy in location that far exceeds those made manually as an example – if users allow them of course. Technology is a significant driver for citizen science projects such as this one aimed at monitoring changes in nature from observations of ordinary people. Most people carry a smart phone – and most people – even the busiest ones - have plenty of 10 second breaks during a normal day.

10. Where is citizen science and nature monitoring heading?

While the field of citizen science is definitely expanding internationally to include still more diverse projects and areas of research, Project Biodiversity Now and the experiences gained in the project point to citizen science becoming increasingly digitalized and technology-based to effectively bridge the gap between hard science and amateur scientist. An increasing number of nature monitoring apps are making use of Artificial Intelligence (AI) for more accurate species recognition and to ease user participation. Artificial Intelligence in this arena is a promising tool because, if applied correctly, it addresses some of the main obstacles and wants expressed by the citizen scientists active in our project. Firstly, we identified lack of species knowledge as one of the main obstacles for NaturTjek users. This could have been addressed using AI, providing users with little or no knowledge of species with the opportunity of letting their phone teach them to recognize species over time. Learning by doing is also very common for modern app use. Most people do not read through introduction app screens, but simply swipe past them. Data from NaturTjek also shows that the descriptive texts and pictures for each of the 30 species received very little attention from users. People want to test out the app first and gain experience through interaction. This, however, conflicts with the research design of many citizen science projects, including ours, which require users to do basic “training” first and only send in data which they are convinced is correct. Using AI addresses another significant drawback in our project – the lack of data verification. Once AI has been properly integrated into an application, it can determine with significant accuracy how many registrations may in fact be considered valid data and provide users with instant feedback, while constantly improving accuracy as more and more data flows into to the system. Something which is of great value for citizens and scientists alike. Greater awareness of the biodiversity crisis internationally and improvements in technology, particularly those surrounding smartphones, form the basis for future citizen science projects within the field of nature monitoring where virtually everyone solely with a desire to make a difference may be able to participate.

Project team